Introduction

This essay discusses how black people appear in science fiction literature and put a spotlight on the genre Afrofuturism. I am an avid reader and aspiring author who loves to be taken into space, whether it’s through film, literature, or music. I’ve always found interest in worlds away from this planet, or in a planet where the strange appears, but I’ve always had issues with finding books with characters who looked like me or had the same experiences I did. When my own books get published, I want to be sure I have characters who look like me and have similar experiences to my own. I want to be able to inspire young children of color to seek worlds beyond their own. For me, it’s been a bit jarring to see characters defending the galaxy in the future yet to have none of these characters be people of color. It’s led me to question why that is.

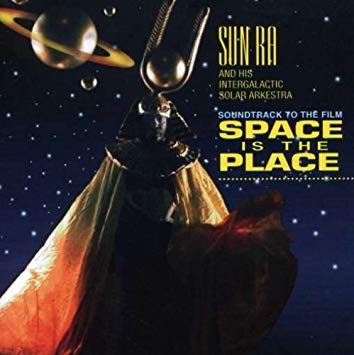

On my journey to understanding why there was a lack of black characters in science fiction, I stumbled upon the genre of Afrofuturism, which led me to the major thesis within this essay. First, I will discuss the definition of science fiction, comparing it to what I’ve uncovered on Afrofuturism. When understanding what Afrofuturism is, I decided to discuss at length one of the first Afrofuturist creators, the artist named Sun Ra, and I use his life and his creativity in order to further explore what it means to be an Afrofuturist creator. I discuss how blackness is experienced as Otherness and how this experience might lead to otherworldly art, as found in Sun Ra’s music and poems. Being an Afrofuturist creator often takes place outside of the margins and I use Sun Ra’s life experiences to further this argument.

Finally, I will conclude this essay by using Sun Ra’s “Otherness” to look at an example of contemporary Afrofuturism in the short stories of N. K. Jemisin. I will use three of her short stories in order to express how an Afrofuturist thinker/creator often lives outside of the margins of society, which grants them a better understanding of their society and alternative ways to fix the issues within them. I want to further this connection of being a marginalized creator by finding reviews of people who critique Afrofuturist’s work and display how most readers do not get a full understanding of their work.

Introduction to Science Fiction

The critic Dr. Beshero-Bondar offers the following definition of science fiction, the genre I focus on in this essay:

Science fiction is a time-sensitive subject in literature. Usually futuristic, science fiction speculates about alternative ways of life made possible by technological change, and hence has sometimes been called “speculative fiction”. Like fantasy, and often associated with it, science fiction envisions alternative worlds with believably consistent rules and structures, set apart somehow from the ordinary or familiar world of our time and place. Distinct from fantasy however, science fiction reflects on technology to consider how it might transform the conditions of our existence and change what it means to be human. “Sci Fi” is the genre that considers what strange new beings we might become—what mechanical forms we might invent for our bodies, what networks and systems might nourish or tap our life energies, and what machine shells might contain our souls (Beshero-Bondar).

Science Fiction is a genre that explores possible alternatives for humanity, sometimes with magic or technological advancements, which is why it can also be called “speculative fiction”. Similar to fantasy, both genres are based on alternative worlds, but science fiction focuses on technology and how it can alter the definition of humanity. When discussing the futuristic aspect of science fiction, we might use as an example the film Star Wars, created by George Lucas in 1977. In Star Wars, we follow the lives of the Skywalker family, from “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away….,” where there are aliens and droids, all fighting to understand the divide between the Rebellion and the Galactic Empire. This beautiful series inspired many people to read more science fiction and to write their own stories, including the author Ytasha L. Womack, who will appears later.

As with most science fiction writers, George Lucas was inspired by the world around him for his film series. He said in an interview with Ty Burr for the Boston Globe, “It’s really based on Rome. And on the French Revolution and Bonaparte.” (Burr). George Lucas also mentioned in the interview that readers from the United States believed the series was about George W. Bush and people from Russia believed it was about Russian politics. Most writers are inspired by the world around them, just as George Lucas was, which allowed people all over the globe to speculate about what could have possibly inspired such a huge franchise. The powerful thing about science fiction is that it is often about real life: real wars, real injustices, or real ideas about where we will be in the future. Most people see the future the way George Lucas did, in the stars and with robot and alien companions. My question is, if science fiction is based on real life and created with an imaginative version of the future, then where are the people of color who naturally fill our everyday lives?

In the entire Star Wars franchise, there are only two popular black characters: Lando Calrissian, played by Billy Dee Williams in The Empire Strikes Back (1980) Episodes V-VI, IX and by Donald Glover in Solo: A Star Wars Story; and Finn, played by John Boyega in The Force Awakens (2015). In a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, why aren’t people of color around? The answer to this could be institutional racism, which is racism expressed in the practice of social and political institutions. This obviously doesn’t encourage the hiring of people of color as actors or writers; nor does it encourage directors to create films featuring people of color in futuristic spaces. The knowledge of institutional racism, and the lack of characters to relate to, led many people of color to try and create their own forms of media—ones where there are characters who look and speak like them, where characters of color are seen as heroes and not simply as sidekicks. For black people, this led to the creation of Afrofuturism, which is what will be explored in this essay.

Intro to Afrofuturism

The term “Afrofuturism” was coined in 1993 by Mark Derry in his essay “Black to the Future” and has been given several different definitions. For example, it was described as “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation” by Ytasha L. Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture. “I generally define Afrofuturism as a way of imagining possible futures through a black cultural lens,” says Ingrid LaFleur, an art curator, and Afrofuturist” (Womack 9). As discussed before using Star Wars, there weren’t many black people in the world George Lucas created. Many other science fiction writers have also lacked in having black characters and black readers, and black writers have decided that they wanted to see themselves in the future. Reynaldo Anderson says in Womack’s book, “What I like about Afrofuturism is it helps create our own space in the future; it allows us to control our imagination” (16). Afrofuturism can appear in different genres: for example, science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, Afrocentricity, and magical realism with non-western beliefs. These genres reimagine history by imagining the future—an imagined world that carries the culture and history of black people into the future.

The Reception of Afrofuturist Work

Black Panther (1966) is a comic book series created by Stan Lee that follows a black superhero who is king of his own kingdom, Wakanda. Wakanda is a technologically advanced society hidden in Africa. The series depicts black characters in the future as thriving, socially powerful and technologically advanced people rather than as people who are living in America today, still stifled and held back by the racial and societal divide. The people in Wakanda are all black and were given a fictional metal called Vibranium, popular for its extraordinary abilities to absorb, store, and release large amounts of kinetic energy. The Wakandan society valued their African traditions; even with their wealth and intellect, they stayed true to their roots. Vibranium allowed the people of Wakanda to hide their wealth and advanced technology from the world. Within this comic book most of the characters, whether superheroes or villains, are black people and the only white people who appear are the side characters.

Afrofuturism has become popular lately because black readers are begging for more representation. In February 2018, a hugely popular film adaptation was made of the Black Panther comics. But we need to realize that it would not have gained as much popularity in the past when racism was more dominant. While there have been some negative response to the film, reactions have largely been positive. “In the group, Down With Disney’s Treatment of Franchises and its fanboys, a moderator created an event titled, ‘Give Black Panther a Rotten Audience Score on Rotten Tomatoes.’” (Verhoeven ). The most negative responses came from a self-proclaimed ‘alt-right’ Facebook group that has since been deactivated after it threatened to flood movie criticism aggregator Rotten Tomatoes with bad reviews for Black Panther (Destra).

In our current political climate, creative pieces that depict black people as heroes are still being criticized. But because our society is beginning to hear and listen to the needs of people of color, there can be a popular film with mostly black characters made in the first place, and it can be fairly positively reviewed. The New York Times describes the film as “buoyed by its groovy women and Afrofuturist flourishes, Wakanda itself is finally the movie’s strength, its rallying cry and state of mind” (Dargis). It was ranked 97% on Rotten Tomato and one comment by Geeks of Color says, “Marvel’s Black Panther film means so much to so many people. The film is a lightning rod of representation, in a time where black people feel so belittled and not paid attention to” (Geeks of Color).

Though Black Panther is a contemporary and successful example of Afrofuturism in film, it is hardly the first example of the genre. For example, Blade (1998), another film with a black main character, got criticized for its poor acting and scenes. Within the late 90s, people weren’t open enough as yet to accept a movie with a black superhero, with the New York Daily News describing the film as “pure hackwork”( Kehr).

At that time, Bill Clinton was president. Four years prior to the release of the film, he signed a bill which promoted mass incarceration. Mass incarceration severely penalized and demonized the black community. To be clear, there is not a direct cause and effect relationship between mass incarceration and the reception of Blade. But it is worth noting that twenty years ago, when the black community began experiencing mass incarceration, which lowered the status of representations of all members of the community by the dominant, white one. Mass incarceration furthered the divide between people of different races, pushing black people further outside the margins of society. The experience of mass incarceration and demonization perhaps played a role in the negative reception that Blade received upon its release. But, through the continued othering it brought about for the black community, it also contributed to the subsequent flourishing of Afrofuturist works in film and other media.

Throughout history, there have been many black people who knew that the majority viewed them as outsiders and who chose to fight again this instead of accepting this new normal. Some became politicians, pastors, and social leaders. Others became Afrofuturist creators, using their art in order to bring a better understanding of black people and the black experience. Most of black history has been silenced and Afrofuturist creators use their history and culture in the hopes of connecting people within and outside of the African American community. These creators allow their minds to stretch far into all of time and space, creating imagined futures where people who look like them are seen as important members of their society.

Music in Afrofuturism

In Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, Ytasha L. Womack describes the many different art forms of the genre:

Whether through literature, visual arts, music, or grassroots organizing, Afrofuturism redefines culture and notions of blackness for today and the future. Both an artistic aesthetic and a framework for cultural theory, Afrofuturism combines elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, Afrocentricity, and magical realism with non-western beliefs. In some cases, it’s a total re-envisioning of the past and speculation about the future rife with cultural critiques. (Womack 5)

For example, Octavia Butler, one of the first black science fiction writers, wrote Kindred—a story about a young girl who travels back in time and gets a first-hand experience of slavery. This novel allows the main character to experience her history firsthand in order to gain a better understanding of her ancestry and her own society. Butler granting her main character the ability to travel through time makes it a timeless piece of Afrofuturism. Although the main character has no crazy technical time traveling device, her going back in time and seeing how her ancestors lived makes it science fiction. Kindred then allows us to understand black history more fully by imagining the future. That’s the power of Afrofuturism, it imagines a black future where the reader can better understand a black history and the current black experience.

As Womack’s quotation makes clear, Afrofuturism is a multi-media genre, appearing not just in literature but in visual art, films, and music. A current and popular creator within this genre is Janelle Monae. A black woman, Monae is doubly marginalized as a woman of color. Like many great Afrofuturist artists, Monae works in different forms: she created a short film based on her album. The film imagines a dystopian future where people get penalized for their expression. This is a common theme in Afrofuturism because these creators use their work to express what they experience in their everyday lives. When Janelle Monae started her career, she was known for wearing tuxedos and her natural hair, which wasn’t how most black female artists would ordinarily present themselves. Now twelve years into her music career, she is still making strides to branch out from what is expected of her as a female creator. In an interview with the New York Times, she says, “The songs can be grouped into three loose categories: Reckoning, Celebration, and Reclamation. The first songs deal with realizing that this is how society sees me,” she said. “This is how I’m viewed. I’m a ‘dirty computer,’ it’s clear. I’m going to be pushed to the margins, outside margins, of the world” (Wortham). Afrofuturist creators often create from a space outside of the “normal” parameters of the world. This world openly tries to silence black voices with police brutality and systemic racism. With social and political movements like Black Lives Matter movement and with artworks from the Afrofuturist tradition, creators are doing what they can in order to promote the community and fulfil their own creative expression.

Sun Ra

It is important to understand how Afrofuturism first started and who its early practitioners were in order to better understand it. And, if we are to consider the history of the genre, then we have to talk about Sun Ra. He was a creator in the 1950s and was born Herman Poole Blount in Birmingham, Alabama in 1914. Sun Ra was a jazz musician who decided to forgo his past and create an imagined persona named Sun Ra or Le Sony’r Ra. As Patrick Jarenwattananon writes, Sun Ra was a carefully constructed identity that “drew from Egyptology, black Freemasonry, Biblical exegesis, science and science fiction and most anything else that lay outside the traditional domains of scholarship” (Jarenwattananon).

Sun Ra grew up with his mother, great-aunt, grandmother, and older brother, and all but his mother valued the words of God, which influenced his journey into music. His grandmother and great-aunt made sure that he attended services and went to Sunday School, and he took his studies in church as seriously as he took his studies in school. In the best full-length biography of Sun Ra, John F. Szwed’s Space is the Place: The Life and Times of Sun Ra, Sun Ra is often referred to as an intelligent child: “He moved quickly ahead of others in his class, meaning top grades in everything… Most of his classmates knew him only as existing quietly on the margins” (19-20). Blount was intelligent all throughout his career as a student and was always eager to learn more. His studies never pushed him outside the margins the way his work did. From a young age, he experienced marginalization and this experience helped make him the artist he became.

His eagerness to learn more led him into a journey of understanding the world around him. Throughout his childhood, he developed the desire to understand Jesus: as he said, “I never could understand if Jesus died to save people, why people have to die. That seemed ignorant to me. I couldn’t equate that as a child” (9). He attempted to better understand the actions of Jesus, paired with his love of music and living in 1940’s Birmingham, “the most segregated city in the United States” (3), are both factors of what gave birth to the name Sun Ra, one of the first Afrofuturist creators.

Sun Ra’s Music and his Arkestra

Sun Ra was known for creating his beats with the sound of hard bops and for his audacious claim to be an alien from Saturn on a mission to preach peace. Throughout his career as a musician, Sun Ra publicly denied ties to his prior identity and his life before taking on this new role as a leader of a new movement. He possessed and made public a vision that would make his work and his style an icon of today. He was a bandleader, composer, arranger, artist, and poet who played jazz, Bepop and Space Music. During the four decades of his career, most of Sun Ra’s past was a mystery. It was not until close to his death that writer John Szwed wrote his study Space is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, published in 1998. Sun Ra encouraged the confusion of his identity by spreading fake and contradictory news about his life during interviews. Indeed, he claimed he was born between 1910 and 1918 but never gave an exact date which gave him the illusion of timelessness.

Szwed was able to uncover that as a young boy, Sun Ra taught himself how to read music and play the piano. From an early age, he showed passion for music. He would go out and see many musicians perform, memorizing sheet music for his school band to practice to. As Sun Ra remembers in Szwed’s book,

My grandmother liked church music so she bought a book with religious songs because she couldn’t believe it either. I played everything in the book. Then my friend William Gray came, who played the violin, and he didn’t believe in me. He said, “I have to study every day. I know it’s impossible just to play music without reading it. You play it like you hear it, and that’s it!” He went home to get sheet music and I played everything that he bought, Mozart, everything, I played it. So from that day on he brought sheet music every day to find out if there was something I couldn’t read. I had to play everything by sight. He couldn’t find anything I couldn’t read. (12)

Sun Ra showed a natural gift toward music and he began composing music a short while after, sharing it in a way that was distinctly his own. Sun Ra knew that his place wasn’t in the church but he did use what he learned during his time there in order to create a new sound.

As previously mentioned, he didn’t feel a connection towards Jesus. Instead, he questioned the motives of Jesus and spent his life trying to better understand his connection to God. Later in life, he reflects:

…I decided since I was making such good marks, there wasn’t no need being an intellectual if I couldn’t do something that hadn’t been done before, so I decided I would tackle the most difficult problem on the planet. I could see how I was progressing on the mental lane, on the intellectual plane, but the most difficult task would be finding out the real meaning of the Bible, which defied all kinds of intellectuals and religions. The meaning of the book that’s been translated into all languages. They could never find the meaning and that’s what I want to do. (28)

Sun Ra’s path into becoming one of the first Afrofuturist creators was inspired by his desire to better understand God. Though Sun Ra showed promise with his intellect, he decided that it would all mean nothing if he couldn’t inspire the world in some way. His studies pushed him to exist outside the margins but it was his art that truly forced him to the margins and perform boldly. As Sun Ra grew older, he began to show promise due to his skill. His former English teacher, Ethel Harper, offered him a full-time musical position in 1934. Sun Ra toured with Harper’s group across the U.S. Harper left the group mid-tour and Sun Ra took over until the tour stopped making income. Yet, in this time, they did acquire a lot of fans. When he returned, he went to study at the Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical Institute for Negroes in the 1930s. As he was in high school, he kept good grades and focused on his music. Through this experience he realized his calling to branch out on his own and create.

In his 1974 film Space is the Place, Sun Ra talks about an experience that caused him to change his name and identity:

My whole body changed into something else. I could see through myself. And I went up… I wasn’t in human form… I landed on a planet that I identified as Saturn… they teleported me and I was down on [a] stage with them. They wanted to talk with me. They had one little antenna on each ear. A little antenna over each eye. They talked to me. They told me to stop [attending college] because there was going to be great trouble in schools… the world was going into complete chaos… I would speak [through music], and the world would listen. That’s what they told me. (Szwed)

Sun Ra believed that he had been abducted by aliens and was given a divine connection to space in order to begin creating music. He used his newfound connection in order to bring connectivity to the black community. As previously mentioned, Sun Ra grew up in a heavily segregated community and he knew firsthand what it is like to be prejudged. He had a gift with music and many people would deny his ability to create to music the way he did. With this visit from space, Sun Ra set off onto his journey to create music and became the creator he is known to be today. Sun Ra had an experience of feeling like the “other” throughout his life because while living in Birmingham, AL, he was poor, and an intelligent black boy which left him on the margins of his school life. During his college experience, it seems that his experience of being abducted was just an amplified version of this experience of otherness and alienness from the world around him. This experienced pushed him further outside of the margins of society sense there is no definitive proof of aliens. His claim to have been taken to Saturn would have understandably ruined his credibility.

Sun Ra set out to create an entirely different sound of music, using many different genres—jazz, Bepop and Space Music—in order to convey his message of peace. He often used his instruments in order to create different sounds. For instance, he used a bass guitar to create the sound of a woman screaming:

…in my music, there’s a lot of little melodies going on. It’s like an ocean of sound. The ocean comes up, it goes back, it rolls. My music always rolls. It might go over people’s heads, wash part of them away, reenergize them, go through them, and then go back out to the cosmos and come back to them again. If they keep listening to my music, they’ll be energized. They go home and maybe 15 years later they’ll say, “Whoa that music I heard 15 years ago in the park… it was beautiful”. (122)

He was an intentional performer; he wanted his audience to experience a trip just as he did when he was abducted. He wanted his audience to leave the mundanity of society and experience the cosmos and then gently return them to Earth. He wanted his work to be memorable. Sun Ra was known for creating his beats with the sound of hard bops and his claiming to be an alien from Saturn on a mission to preach peace. Throughout his career Sun Ra experienced many bouts of loneliness, which is to be expected since he is the only creature who has claimed to have been visited by aliens and based his career on this. Through his experience visiting Saturn, it is assumed that he gained the ability to create Space Music because of his visit:

Those who live the jazz life, those who dwell and create on the margins of society and art, who toil on the real graveyard shift of life, whose art is rewarded less with fame than notoriety, develop means for dealing with it: brilliance, madness, hip talk, worldly polish, simple withdrawal, disdain, obsessions, addiction, a whole panoply of defenses, evasions and shields. (Szwed 97).

Traditionally, working in the Jazz life is a lonely business. While creating outside of the margins, one would also find themselves desiring to be valued within the margins. When there is still trouble being accepted within the society, the natural response is to become more reclusive and falling into the safety of their own security, which is the case for most Afrofuturist creators. Sun Ra did feel a connection towards his Arkestra because they lived together. But none of them could understand him and his connection to the otherworldly, which led him to bask in his “onliness”—a phrase that is found in his poems in the next section.

Sun Ra’s Poetry

Sun Ra is most known for his musical performance and outrageous outfits; most people don’t know that he also wrote poetry. Sun Ra would perform his poetry in front of an audience, giving off the same otherworldly feel of his music and style. He was an Afrofuturist creator which allowed his work to be otherworldly and see the world from a different point of view. Living in a world that doesn’t want to hear the voices of black creators, Afrofuturist creators are given a gift: the gift of being able to connect with anyone who feels like they are living on the outskirts of their society. Sun Ra embodies this theme in these three poems: “The Other Otherness,” the original written in 1972 and another version written in 1980, and “Other Planes of There, written in 1980.

In his poem “The Other Otherness” (1972), we can see how Sun Ra views the world from the point of view of the “other.” Looking at the title, we can see the emphasis he puts on the words. During Sun Ra’s years of creation, he saw himself as the other of otherness. Sun Ra has a vision of being an alien on earth brought to preach peace, forgoing negativity and hate in order to bring forth love, truly making him the other of otherness and living outside of the margins, as Janelle Monae has previously said. Many black men during this time spoke of preaching peace, like Martin Luther King Jr. Sun Ra and MLK are black men who were living outside of the normal parameters of society. They chose, in their own ways, to promote love within the black community and showed people of other races the multiplicity of black people. Sun Ra was such an outrageous and out-there black man, living in his truth, he was separate and living in “onliness,” for he is the only one living this life. Not only was he deemed crazy or a drug user because of his truly out-there behavior; people would run away from his performances. Some people did not understand that this jazz musician wasn’t just playing Jazz. Sun Ra chose to bring peace and love from Space with “no ego” (line 2) and no communication for those were made with love will bring forth love.

Within this same poem, Sun Ra uses the phase, “To feel our worthless pricelessness” (line 9). This is such a contradictory statement, for something to have no worth and also be priceless, valued. It’s such a confusing statement at first glance but once analyzed, it can be seen as Sun Ra seeing his work and himself as priceless. His creativity and his new way of making music is priceless. He uses instruments in order to create screaming sounds. Most people listened to his music and thought he was insane or on drugs for orchestrating such chaotic music. The value most people placed on his sound was worthless. This is why he isn’t mentioned in today’s media as a valued creator. The majority chose to ignore his sound in favor of classical jazz music. This ties in with Afrofuturism because science fiction is being normalized: we have started seeing science fiction appear in more television and films but there is difficulty finding pieces of media that have black people as the main character in these films. For some science fiction lovers, having characters of color isn’t very important but for the small portion of us who love getting our hands on a book that has people with brown skin and cultures that relate to their own.

This poem begins by discussing being “the other of otherness,” so far removed from a society, truly living in the outskirts of everything. Science fiction is still such a weird topic in many social and literary circles. It’s hard enough chatting about your love of aliens from other worlds. Now imagine talking about your love of black aliens. Get ready to crash and burn at that social gathering.

Sun Ra writes, “There is no communication/ In the supervised state of distances/ For we who are/ Know we are to is/ To be” (lines 5-7). This seems to mean that in order to become this other, you must forgo your ego and not communicate because those who are other naturally know how “to be,” As previously mentioned when discussing Janelle Monae, “This is how I’m viewed. I’m a ‘dirty computer,’ it’s clear. I’m going to be pushed to the margins, outside margins, of the world.” She is living her life outside the margins; she is being outrageous in a time that views her as a “dirty computer”. Sun Ra has been viewed as weird because of his sound and as he dresses, he acted outside the assumptions of a black person in the 50s, making him another “dirty computer.”

Often within this poem, Sun Ra writes as if there are more people who are on the same plane as him, as he uses “we” and “our” but then uses “only” and “onliness.” The loneliness of not being seen by the majority also suggests how rewarding it must be to have traveled with so many people who were living in the same plane. His world, his people, seem to be in a bubble—free and out-there creators.

Throughout his entire career, he never got the success he deserved for being so far out of societal norms. My family, who was around during his rise, gave me mixed comments. My parents loved his work, but I have older cousins who judged his work and assumed he and his Arkestra were all on drugs. His work was dismissed and most people didn’t understand his vision. He was around before many well-known jazz musicians like John Coltrane and Miles Davis but his work wasn’t as appreciated. Most people don’t even know who he is or that his Arkestra is still performing to this day.

I believe his space persona was his way of alienating himself. He knew that his vision and his sound would place him out of the norm but he followed his dreams anyway. He lived as an outsider with a passion, a dream. He grew up with his family alienating him because he chose not to continue his education in school or go into the military. Instead, he chose to leave his family and create.

Sun Ra revistits this poem two other times in 1980. I want to focus on his version 1. In this first version, he once again focuses on the word “Onliness,” a combination of only and lonely. There seems to be a lot of solitude in his creative journey into space. In this poem he writes, “Movement out to behold kindred otherness / Of and from other worlds /Beyond worlds………./ … ./ Beyond worlds ……. Beyond worlds beyond worlds” (line15). The great worlds beyond will hold the otherness he seems to be searching for. Sun Ra often felt that the creativity for his work needed to be found in another world. No one during his time made music that was even remotely similar to his music and, in order for Sun Ra to find inspiration for his work, he had to look outside of himself.

In version 1, Sun Ra uses a lot of ellipsis in this poem as seen from the quote in the previous paragraph and in this: “to rise above the earth’s tomorrowless eternity…..” (line 7) It seems like the use of ellipses in this stanza is to express that he is trapped in some sort of endless cycle. His onliness is leaving him in a world with a “tomorrowless eternity,” a living with no end. This could be in relation to Sun Ra’s reality. He was alive during the aftermath of Jim Crow America and the Civil Rights Movement. In his life, Sun Ra did what he could to help his community: he would invite artists into his home and Arkestra with the hopes of getting them on their feet and getting shelter and security. He also took in people who did drugs, though he did none himself; he simply wanted to support his community. Putting that much pressure on himself to support his community and produce his music that wasn’t very well received could have possibly taken a toll in him leading him to feel like life was a “tomorrowless eternity.” When will the bright light at the end of the tunnel show itself?

Sun Ra’s feeling of loneliness is often how it is to be an Afrofuturist creator. Afrofuturism is a multi-formed genre that embodies the black experience in a different light. Afrofuturism isn’t what white people or other races believe the black experience is; it is black people writing about their own experiences and very often, the feeling of exhaustion and the hopes of being recognized for our hard work and craft often comes up. The society we live in has not valued the work of black creators the way they do white creators. It is especially hard when the creator is like Sun Ra and they branch outside of the expectations of the society. There is a different kind of “onliness” when the majority doesn’t understand your motives.

In Sun Ra’s poem “Other Planes of There” (1980), we see similarities to the other two poems. Within this poem, we are actually branching into a part of what Afrofuturism is. Sun Ra writes, “And from the future/ Comes the wave of the greater void” (line 5-6). This means the “greater void” is the future, the unknown. Sun Ra had no idea what the future would hold for his work or the future of the black community. He didn’t know if all his work would be greatly appreciated or if people would still view his work as “worthless.” He also writes, “The displaced years/ Memory calls them that” (lines 1-2), forgotten as Sun Ra feels as if he is forgettable. He has worked years on his music and his sound without getting the success he deserved. People would run out on his music because his sound was too much to hear. From reading his poems, it seems like Sun Ra often felt like his work wasn’t as important to the world as it was to him. He spent years being undervalued for his work.

Sun Ra later writes, “They were never were then”, which means that they never were memories; they never were displaced or forgotten. This line is fragmented, as his memory seems to be. He later says, “Memory scans the void” (line 4). The void here seems to be a vast emptiness, which ties into him saying that the greater void is the future. He follows this by saying, “A pulsating vibration/ A sound span and bridge/ To other ways/ Other planes there” (lines 7-10). I think what he says is that his sound is what connects the displaced years and the great void. The sound is what brings him back. It ties into his previous poem, where he mentions “onliness”; there is still a piece of solitude within this void. His sound is what brings him back from the void, the “Onliness.” He calls it “A pulsating vibration” (line 7) and “A sound span and bridge” (line 8). The bridge is what he needs to get him centered, back to the present; it is what allows him to move beyond worlds. Sun Ra used his art to carry him between the mundane and the world beyond, which is similar to Afrofuturism.

Afrofuturism moves beyond the world of the majority and focuses on the minority, the voices that aren’t often heard—the experiences that we don’t normally understand in mainstream media. Sun Ra’s music moved beyond worlds, too. His listeners were used to mainstream music; his sound was heard in small bars and clubs unlike John Coltrane who performed at larger venues but he believed that his songs needed to be heard. As previously mentioned, Sun Ra’s sound comes in waves: he begins his work with the classic sound of jazz which has a smooth ebb and flow of sound then he lifts off into space and plays his funky space-sounding music that is so otherworldly that many people ran out in fear. If you stayed with him along with this journey though, he brings you right back down to the Jazz that you know and love. He brings you back to earth which is what Afrofuturism does. It takes what we see in popular works, what we know and love, but adds people of color into the work and continues the story as it normally would be. The story of someone’s life but in another world or another space, we see it in pieces written by N.K. Jemisin, in particular in her short story collection How Long Til Black Future Month.

Understanding Afrofuturism Through a Contemporary Lens

Sun Ra gave birth to decades of Afrofuturist creators, as many black creators want nothing more than to see people who look like themselves in futuristic or powerful positions. One author that will be explored is N. K. Jemisin who is the author of nine books—two trilogies, a duology, and now her collection of twenty-two short stories. She is a three-time Hugo award winning author who writes within the genre of speculative fiction. In How Long Til Black Future Month?, Jemisin writes about her anxieties writing within the genre of speculative fiction because there weren’t people who looked like her within this genre. In an interview with The Paris Review, for instance, she says,

In Star Trek, in the future, everyone can be part of the Starfleet. Supposedly all of humanity has access to good education, good food, all of that other stuff, and yet, Starfleet is still dominated by middle-class, middle-American white dudes. So, something happened along the way, clearly. There’s only one Asian man and Asian people represent the bulk of humanity now. That’s crazy. (Bereola)

This is very similar to what was discussed with Star Wars, where there is a disparity within the possible future of humanity. Everyone within this society seems to be flourishing; they’ve solved the economic and financial issues within our society but the characters who are seen as the heroes are predominantly white and the only character of color is Asian and apparently Asian people are the majority within this society. Jemisin acknowledging this disparity shows that she can see from the outside of the margins. She can acknowledge when there is an issue within this fictional society which is also apparent within our own society.

N.K Jemisin’s writing embraces what we have seen with Sun Ra: Afrofuturist creators struggle with finding their place within the society and it shows in their work. We saw with Sun Ra’s poems that he felt like he was creating “beyond worlds” because other black artists were playing music that was accepted by the majority. Many creators before and after him were popularized because they created work that was valued more. For creators within any genre or form of media, when the society undervalues you because of how you look or speak, you gain the ability to see the world in a new light.

Although it can be a difficult and frustrating journey, there is power in being unseen or underappreciated. Jemisin realized her power in wielding her otherness. She speaks about this in her interview with The Paris Review:

Maybe because I am a black woman, there is an automatic assumption that I am somewhere in the margins of science fiction, in the margins of fantasy, and therefore people from outside of the genre’s margins are a little bit more willing to take a look at me, even though I’m writing solidly science-fiction stuff. (Bereola)

Jemisin says that, because she is a black woman and is somewhere within the margins of science fiction/fantasy, people outside the margins are willing to try and understand her and her work because she only writes Speculative Fiction. She expects people to see her as “other” and finds herself being more accepted as being a writer as the “other.” Those who live outside the margins of society have an understanding of how the world could be different. Living outside the margins of society helps bring out the ability to imagine or see other worlds and other ways of being. N. K. Jemisin’s stories feature underappreciated characters who are able to see beyond worlds and truly make a change within their society.

“The City Born Great” by N. K. Jemisin

In her collection of short stories How Long ‘til Black Future Month?, Jemisin examines modern society and infuses magic into the mundane. In a review for Tor.com, Martin Cahill writes:

…the majority of How Long ’til Black Future Month? is not only about characters of color being given the opportunity to see the systems affecting them, but also giving them the chance to seize the power that runs those systems, and use them to protect themselves, safeguard their communities, and write their own futures. (Cahill)

Jemisin allows black characters to be seen as the saviors, as superheroes or simply as beings within a society where they are not seen in most works of science fiction. She gives her characters the opportunities to “seize the power” that runs the system. It’s what is found in Sun Ra’s music and it is a powerful element in Afrofuturism.

A short story in the collection title “The City Born Great” has a main character who becomes the “midwife” of New York. The story follows the character who undercovers the truth of New York, which is that the city isn’t a just a city: “Great cities are like any other living things, being born and maturing and wearying and dying in their turn” (How Long 20). Just as Sun Ra mentions, there are strange things within the mundanity of the world but it takes someone who is already on the outskirts of the society in order to see it. Jemisin embodies that within this story. Using that description of the way cities operate within this world, the cities need a “midwife” to connect with and protect them from the dangerous beings created to destroy them.

In the beginning, our unnamed main character is told by their mentor Paolo to listen—to listen to the street as it breathes. He didn’t believe Paolo until one night, as he was graffitiing a mouth hole on a wall, he finally felt connected to the city. It was through his creation of art that he found a connection to the city. Sun Ra experiences the same as do many Afrofuturist creators. As a person who does not feel connected to the world around them, our main character gets invited to a cafe with his mentor and he notices how the occupants watch them: “The people in the cafe are eyeballing him because he’s something not-white by their standards, but they can’t tell what. They’re eyeballing me because I’m definitely black, and because the holes in my clothes aren’t the fashionable kind” (15). He realizes that he is the other within the society he was born into. Within this setting, he feels misplaced and he knows that those around him would like for him and his mentor to leave in order for them to maintain their carefree environment. He later says, “I don’t stink but these people can smell anybody without a trust fund from a mile away” (15). He believes that they can all tell that he isn’t one of them by their own senses. No one in the cafe needed to mention him or his attire in order for him to feel unwelcome; he just feels it.

After graffitiing, he feels breath on the back on his neck and he knows that he is listening for the sound New York makes when you really listen. After that moment, he goes out every night to draw a breathing hole on every wall, using his art in order to connect and support the city. He feels very unsure about his place as a midwife for the city, even after he is convinced by his mentor, because his only living parent abandoned him. He lives outside the margins of society, homeless and often looked for a place to live. He often finds sanctuary with his Mentor Paulo but he often feels like he should remain unseen, not knowing where his future would lie. He feels like he wasn’t that important for such a huge task but he finally knows he is connected to his place when finally faced with the terrifying dangers of the city.

In this story, cities work differently: “As more and more people come in and deposit their strangeness and leave and get replaced by others, the tear widens. Eventually it gets so deep that it forms a pocket, connected only by the tiniest thread of… something to… something. Whatever cities are made of” (20-21). The people coming into the city and creating a connection that feeds the city is like an umbilical cord that feeds a “child” in the womb. The more people that stream in, the faster of the city grows, pulsing like a heartbeat: “The gestation can take twenty years or two hundred or two thousand, but eventually the time will come. The cord is cut and the city becomes a thing of its own, able to stand on wobbly legs and do… well, whatever the fuck a living, thinking entity shaped like a big-ass city wants to do” (21). In the meantime, it needs its Midwife to protect it against the beings that wait to kill the city before it gets to its maturity. The main character gains the ability to see how the world is connected and to also see what is trying to destroy the city and fight against it. He gains the ability to feel and hear the city’s breath and to feel the pulsing vibration of the city. When he is truly connected to the city, he is able to use public transportation and the natural flow of the city as a weapon against the beings who want to destroy the growth of the city.

Throughout the story, he tries to hide from police officers and other authority figures. When leaving the cafe where he met with his mentor, he runs into a police officer and mentions, “I imagine mirrors around my head, a rotating cylinder of them that causes his gaze to bounce away” (16). He later acknowledges that there is no real power in willing them away; he just does it to try and make himself less afraid. He often tries to think of himself as small and insignificant in order for the police officers to stay away from him. This relates to our society today: where police officers will see a brown face in a sea of white faces and decide that the one brown person is up to no good. When our main character is seen by a police officer, he tries to will their eyes away from him. It has always worked until one of the beings who want to destroy the city come after him disguised as a police officer. In a direct connection to Afrofuturism, a genre that uses fantasy and SF to think about and through black experience, racial profiling plays a crucial role in this story. The monster who has been lying in wait uses racial profiling in order to get police officers to stop our hero before he gets away. Our main character is able to get away from this parasite by running into traffic and using the natural flow of New York in order to run it over. He says, “My city is helpless, unborn yet, and Paolo ain’t here to protect me. I gotta look out for self, same as always” (25). It seems like his instincts are telling him that he needs to protect his unborn city even though he doesn’t exactly know how and so he runs for safety. After he feels that connection to the flow he remembered that what he’s doing is a part of an ancient battle—an actual battle. You can see our character as a mother protecting a child as natural as anything. He runs through the streets of New York after he discovers the monster in police clothing. Many black people experience racial profiling in their everyday lives and for Jemisin to write her monsters disguised as a police officer who is determined to catch a black person. This story gives a fantastical spin to an experience black people face everyday: racial profiling.

This ties into what we learned about Sun Ra: he felt a connection to music from a very young age, just as our main character felt connected to art and therefore the city: “I’m painting a hole. It’s like a throat that doesn’t start with a mouth or end in lungs; a thing that breathes and swallows endlessly, never filling” (17). As previously mentioned, the main character begins to feel more like a midwife for the city when he starts drawing breathing holes throughout the city in order to bring life to the city. For Sun Ra and the main character, a connection isn’t all that was needed for them; they needed to tap out of the mundanity of this Society. They needed to branch into a deeper understanding of the world around them in order to protect what they loved. Sun Ra used his deep love of music in order to bring people to a higher level of being and the main character in “The City Born Great” uses his connection to the city to protect what was important to him instead of ignoring his connection. They use their ability to see beyond worlds in order to encourage and protect the majority.

“Brides of Heaven” by N. K. Jemisin

The second story that falls in alignment with Sun Ra is called “Brides of Heaven.” In this story, we see a colony that traveled from Earth in order to find a new life on another planet. The only issue is that the male population died on the way to the new planet:

…when they’d emerged from the coldsleep unit naked and healthy and horrified to discover that the men’s unit had malfunctioned, Illiyin Colony had been dying. Oh, there’d been hope for a Time, in the form of the boy-children who had shared the woman’s unit with their mothers: Dihya’s Aytarel and two others. (186)

Their last remaining hope for their colony survival died with those boys. All three boys died accidentally, one from drinking contaminated puddle of water, and the other two from childish incidents like falling after climbing a bookshelf. The story we follow is Dihya’s. She is known as the crazy person within their colony. After losing her son she stole a “landcrawler” (186), which is a form of transportation, and went to find a way to revive her colony by finding God on the planet. She succeeded and she was able to find a sentient pool of water that was able to put life into her womb.

Within their colony, they all rely on the word of God. They live in a society of Muslim women who start to lose faith in God because of the death of all those men and children. Dihya mentions that “She could never believe God would leave them to die alone on this planet” (191). She begins to criticize the women who do believe that they’ve been abandoned on this new planet, “That one is a sinner. She lies with other women” (189). The response for this is “Many in the colony have committed that particular sin” (189). Without men, the women within the colony resort to acting out of “sin” in order to adjust to this new way of life, believing that, because God has abandoned them, they can receive some allowance in building more intimate relations with each other.

They are told that men and women complement each other, which is why they need men in order to sustain life. This is true on a biological understanding, but Dihya wants to find another truth. She wants to find a silver lining to all the sadness in chaos. After all, moving to an entirely new planet with no way of communicating to the place you once called home and knowing that every living being within your colony will die with no one to replace them is a sad concept to accept ,which is why she refused to. As shown in Sun Ra’s work, Afrofuturism is used to challenge the way most people view the world, instead deciding to look for the strange within the ordinary and to seek alternatives found in the world. Afrofuturism and science fiction are one and the same. If you understand and enjoy the workings of SF, it’s all found here. The story is literally placed in another world, a future where a colony of Muslim women find a home on another planet. It uses religion and questions a possible future where a religion that most people hold close to their hearts can morph after the feeling of abandonment.

The story is told from the perspective of Ayan, the leader of the community who is tired and unhappy with the realities they face. There is no contact from Earth for another millennium and they have no way of reaching out to anybody to tell them that they may die on this planet and all of that responsibility weighs her down. But when Dihya returns and breaks into the Colony, she takes the time to listen to her story, which ends up being eerily similar to an Amazonian myth. The Amazons are a female-ruled society with women who were able to defend themselves and were self-sustaining, with no need of men because “when one of their kind wanted a child, she went into the forest and found a sacred pool. When she waded in it and prayed, God sent a child into her room” (193). Dihya finds a way to continue living within her colony without men. Before leaving, she would tell stories to children and other women about the Amazons—women who are able to sustain life and their community without men. These women were able to protect themselves and to live a peaceful existence with no need of man. Her telling stories makes everyone believe that she is crazy because all they know is that they need men in order to continue living. As the story continues, Dihya’s audience begins to panic because they see her as crazy; by the end, they wonder what she put in the communal water supply.

An enjoyable quality at the end of this story is that it leads the reader to wonder if the water she put in the water supply will kill the Colony or will give birth to a new species. Caution would suggest that on Alien Planet, one should stay away from water that is conscious. But for Dihya this is a sign of God. It was her own calling that led her leave the colony to search for an alternative way to save everyone. This is in alignment with Afrofuturist creators, who often have the desire to produce a creative piece in order to move themselves or their community forward and although the world may decide that their work isn’t good enough, as was the case with Sun Ra. There is power in continuing on that path in order to support the community.

Her intentions were to save her community because she saw that everyone was unhappy because they all believed they would just die out and no one would come to save them until years after they’ve all died. For Dihya, being the protector or savior for her community could have in fact damned them. It remains unknown whether her journey to the pool was God showing her the way to save everyone or if it were a sentient being who simply wanted to kill them all. After traveling to an unknown planet and learning that half of the population has been killed is difficult to digest. Then realizing that the only way to sustain the society relied on three young boys one of which was her own child. That is a lot of pressure to place on a woman and a child so young; when he died the only obvious way to move forward was for her to find what God meant for her in this world.

Being deemed the crazy person in her society, Dihya is able to go out and break the rules in order to find a way to support everyone. This story follows an outsider, someone who lives outside the margins of society who gains access to the deeper truth because she chose to steer away from what is “normal.” This is in relation to Sun Ra’s work and creators of Afrofuturism: being seen as “other” within your society, one gains the ability to see beyond the traditional world and gains the ability to see beyond worlds.

“The Elevator Dancer” by N. K. Jemisin

In the final short story, “The Elevator Dancer,” we are able to see the inner workings of someone who is ready to branch out of the “normal” and begin to think outside of tradition due to an outside influence. Afrofuturist creators don’t just wake up and become these creators; there is always an influence, something that awakens the soul and encourages change. Within the previous stories, both main characters had an influence that spurred them on: in “The City Born Great,” the main character had Paolo; for Dihya in “Brides of Heaven,” she had the death of her son. For these stories, we were either told after they step out of tradition or the main character was encouraged into this new step. “The Elevator Woman” has a character who branches out on his own, oblivious to stepping out on his own but thoroughly entranced by the movement of someone known as the elevator woman.

This is the shortest story within this collection but also one of the most provocative. The story opens with a man shocked to find a woman dancing in the elevator. He admires her dancing, which reminds him of the dance moves his mother used to do. He is so shocked and entranced by this woman that he thinks about her even when he goes home. At home, he leads a mundane life in what we come to learn, is a dystopian society: a society ruled by a leader who monitors all that the citizens are doing. Their world is filled with prayer and organization. The story’s protagonist goes home; he eats dinner with his wife; he washes dishes; and he thinks about the woman dancing. He watches TV with his wife and then during the “prayer-and-commercial break,” he thinks about the elevator woman, wondering what she prays for. That night he has a “lackluster orgasm” (235) with his wife and is still consumed with the thoughts of this elevator woman.

As the days go by he still looks at this woman on the elevator. Their elevator has a camera within it and he notices when the woman dances. He notes that she will only dance in the elevator when she is by herself; whenever she is on the elevator with anyone she is still and acts like a normal civilian. But when she is by herself she dances and every time she dances it is always something different. She will pirouette; she will do the mashed potato and anything she feels likes doing by herself. He thinks of this woman so much that he believes that she could never be married and even wonders how it could be if he married her. His fixation on this woman leaves him to question God and his motives:

… he begins to believe that God has sent her to reach him. The pastor’s words, from Wednesday night Bible study… If a tree falls in the forest and there’s no one around to hear it, it makes a sound if God wills. The elevator woman is that sound. She exhaults him and inspires him. She fills him with fervor he believes is holy. To dance with her is to embody prayer. He weeps as he tries to find her and fails. (236)

He becomes so obsessed with her that he finally tries to go and speak to her. He tries to build a connection with the strange woman dancing in the elevator but when he goes to speak to her he finds that she isn’t there; from looking at her in the monitor and running to the elevator doors, she has vanished. The reader learns that within this dystopian society, those who go on “psychotic breaks” like this get help. And because he has been a good American all his life he just has to go to a camp and in this camp, he learns that the elevator woman was just a hallucination and that he has misplaced his faith. When he returns from the camp, he goes back to his job monitoring the elevators but he still wonders. He questions:

It is shameful and sinful to question the will of God. Still, the guard cannot help wondering. He does not want to think this thought, but sly, like temptation, it comes anyhow. And well…

If…

If a tree falls…

If a tree falls and there’s no one around to hear it (but God)…

would it really bother with anything so mundane as making a sound?

or would it

Dance. (237)

The story is different from the other two because our main character isn’t the one making a change. The main character becomes obsessed with this strange elevator woman; the movement of her body makes him begin to question God’s motives. He lives in a restrictive society that doesn’t allow dance or love. When seeing this woman dance in the elevator for the first time, “He does not alert the police, who these days concern themselves with other things besides crime. He simply stares as she twists her feet and hips over and over, bopping her head, too, in time to her own internal rhythm” (234). He later goes home wondering if the police will come for him for watching her. He questions if she has an “assigned” (236) husband but realizes that she couldn’t because she is employed. Him mentioning having assigned partners gives the reader the impression that there is no love between them and without love and with dancing being illegal, as you find out later on, one would imagine that there is no imagination within their world. One would begin to wonder what happens now that our main character has started questioning their society.

This short story is interesting because it shows what could happen in a society before a character begins to see outside the margins. Now that he has seen or hallucinated the elevator woman he is now marginalized; he went to a camp where they try to convince him that the elevator woman was all in his head. After serving his time, he returns to his position as security guard and is still wondering how he could connect the movement of that woman’s hips to the movement within his own society. Now that he has seen beyond his understanding of the world, he now questions the structure of it all.

Each story displays a character who appears to live within the margins of their society. They use their place as the “other” in order to question and then possibly influence the people around them, just as Sun Ra did. These stories display a fictional creation of Afrofuturist creators. There are many people of color who live outside of the margins of society but try to do anything they can to be accepted by the majority. Afrofuturist creators decide to see their “otherness” as power instead of as a weakness and they wield it to change, encourage or support their society. Dihya in “Brides of Heaven” uses her ability as an outsider to give her colony a chance at a future instead of allowing them all to wither and die without anyone knowing for millennia; the main character in “The City Born Great” wields his new connection to the city to force out the creatures who tried to destroy it; and the main character in “The Elevator Dancer” refuses to believe that the woman in the elevator was just a figment of his imagination. Instead he chose to hold on to the memory and question the society. The power of Afrofuturist creators is that they chose to use their work to fight against the world that is holding them back.

Conclusion

The reason I wanted to do this project was because I have a great love of science fiction, but I’ve rarely found characters of color within the stories I’ve read. If I did find these characters, they were always side characters or would be killed off soon within the series. I got pretty fed up because I admire female characters like Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, but I started to wonder what it would take to finally see a black Katniss. I questioned how I could see a bestselling series become a blockbuster movie and have predominantly black characters. I started wondering why there weren’t black people in many books or films and how I could get my own work out there and how many obstacles I’d face on my journey.

I found it imperative for me to look into the past to find out what it took to become popular figures within the genre of science fiction, specifically as a black creator. There are still issues today that set the black community back from becoming popular creators but I believe that as a society, we are making strides to become better and more accepting of stories written by creators who live outside the margins of society. There are safe creative spaces for people who aren’t accepted within the margins of societies in order to create, and I hope that upcoming creators do not feel the isolation and “onliness” that Sun Ra felt.

Because Science Fiction readers and publishers are predominantly white today, there are still barriers blocking black writers from further publishing their work, and this obviously discourages many people of color from writing in the first place. In many literary texts, there are black characters who are used as tools in order to spur on the white main character. These texts are created to connect primarily with a white audience; most texts don’t try to directly connect with a black audience, which is why Afrofuturism has been created. This genre encompasses the fantastical and visionary exploits of the future of black culture and black people. There are more Afrofuturist creators who have surfaced today and are being valued for their craft instead of being deemed as crazy the way Sun Ra was.

Bibliography

Bereola, Abigail. “A True Utopia: An Interview With N. K. Jemisin.” The Paris Review, 3 Dec. 2018, www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/12/03/a-true-utopia-an-interview-with-n-k-jemisin/.

Beshero-Bondar. “Science Fiction – Greensburg Campus: What Is Science Fiction?” LibGuides, pitt.libguides.com/scifi.

“’Black Panther’ Stresses on Imagination, Creation and Liberation.” The East African, 9 Feb. 2018, www.theeastafrican.co.ke/magazine/Black-Panther-movie-review-NYT/434746-4298190-gq2a6v/index.html.

Burr, Ty. “George Lucas Interview.” Boston.com, The Boston Globe, archive.boston.com/ae/movies/lucas_interview/.

Cahill, Martin. “Community, Revolution, and Power: How Long ‘Til Black Future Month? by N. K. Jemisin.” Tor.com, 28 Nov. 2018, www.tor.com/2018/11/27/book-reviews-how-long-til-black-future-month-by-n-k-jemisin/.

Dargis, Manohla. “Review: ‘Black Panther’ Shakes Up the Marvel Universe.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Feb. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/02/06/movies/black-panther-review-movie.html.

Desta, Yohana, and Yohana Desta. “Rotten Tomatoes Is Fighting Back Against White Nationalist Black Panther Trolls.” HWD, Vanity Fair, 2 Feb. 2018, http://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2018/02/rotten-tomatoes-black-panther-facebook-group.

El-Mohtar, Amal. “Gorgeous ‘Black Future Month’ Tracks A Writer’s Development.” NPR, NPR, 29 Nov. 2018, www.npr.org/2018/11/29/671583610/gorgeous-black-future-month-tracks-a-writers-development.

Jarenwattananon, Patrick. “Act Like You Know: Sun Ra.” NPR, NPR, 22 May 2014, www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2014/05/22/314363815/act-like-you-know-sun-ra.

Kehr, Dave. “PURE HACKWORK IT’S A VERY DULL ‘BLADE’ INDEED AS WESLEY SNIPES TAKES ON THE UNDEAD.” Nydailynews.com, 21 Aug. 1998, http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/nydn-features/pure-hackwork-dull-blade-wesley-snipes-takes-undead-article-1.819050.

Knipfel, Jim. “Angels and Demons at Play.” Believer Magazine, 19 July 2017, believermag.com/logger/angels-and-demons-at-play/.

Miller, Laura. “The Fantasy Master N.K. Jemisin Turns to Short Stories.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 Nov. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/11/30/books/review/nk-jemisin-how-long-til-black-future-month.html.

Ra, Sun, et al. Sun Ra Collected Works. Phaelos Books, 2005.

Sun Ra – Space Is the Place – Establishing Contact, www.establishingcontact.org/Sun-Ra-Space-is-the-Place.

“Sun Ra: Space Is the Place.” The Sound of Now, 18 July 2009, thesoundofnow.wordpress.com/2009/01/10/sun-ra-space-is-the-place/.

Szwed, John F. Space Is the Place: the Lives and Times of Sun Ra. Mojo, 2000.

Verhoeven, Beatrice. “’Black Panther’ Rotten Tomatoes Score Sabotage? Anti-Disney Fan Group Takes Aim.” TheWrap, TheWrap, 1 Feb. 2018, www.thewrap.com/alt-right-facebook-group-wants-to-sabotage-black-panther-rotten-tomatoes-score/.

Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture / Ytasha L. Womack. 2013.

Wortham, Jenna. “How Janelle Monáe Found Her Voice.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 19 Apr. 2018, http://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/19/magazine/how-janelle-monae-found-her-voice.html.

Leave a comment